How the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities is fighting climate change from the forest floor to the global stage

It was all going according to plan until Customs got involved. In the months leading up to the 21st session of the UN climate change conference (COP21), scheduled that year for Paris, leaders of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities had planned to converge on the French capital and hit the Seine in a canoe brought from the Amazon. The idea was that the group, representing Indigenous and local community organizations managing some of the world’s largest tropical forests—and whose members tend to navigate their remote homelands by canoe—would send a message to the decision-makers that, as keepers of critical carbon stores and frontline victims of climate change, they demanded a seat at the table. One look at the large wooden vessel, however, and the French officials began drilling holes to check for illegal drugs. The alliance needed a new plan of action.

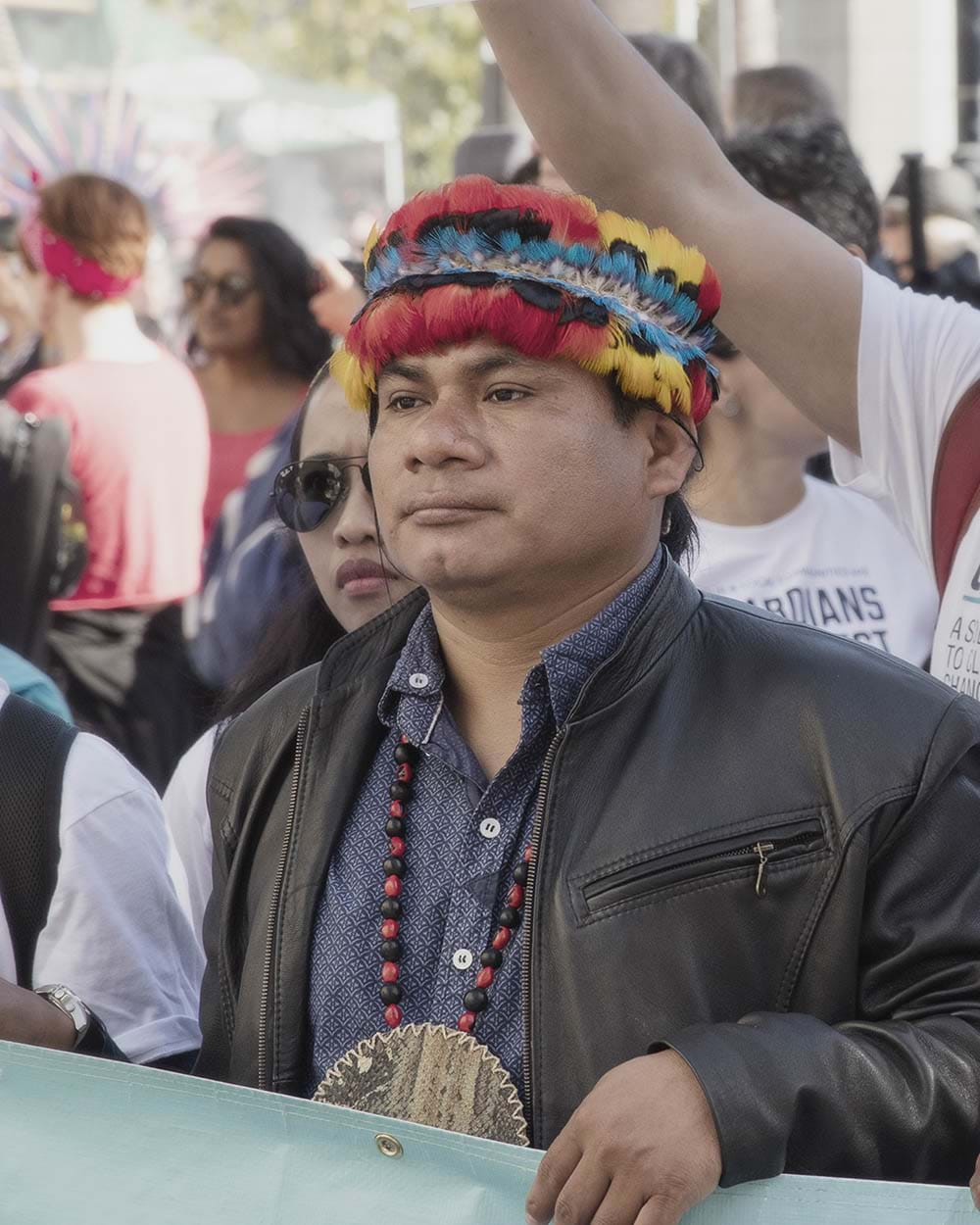

On the morning of December 6, 2015, representatives from villages in Brazil, Indonesia, Costa Rica, and beyond pulled on borrowed parkas and woolen hats and crammed onto the deck of a tourist ferry plying the waters of the Seine. Handmade silk-batik flags carried by tribal peoples fluttered in the wind above the boat as it glided under the city’s famous bridges, hung with banners reading “Guardians of the Forest” and crowded with cheering onlookers. Nearby, Indigenous groups from across the globe joined the action the alliance had dubbed #PaddletoParis by navigating the city’s canals in kayaks. Candido Mezua, an Emberá leader from Panama, said it was the solidarity of the moment that enabled him to brave the 39-degree air clad in only loincloth and ceremonial beads. Twenty-two-year-old Diana Rios, who traveled five days by canoe followed by 10 hours in a car and 12 in a plane, was determined to tell the world about the threats facing her Peruvian homeland, where a year earlier her dad, Jorge Rios, and uncle, Edwin Chota, had been murdered for defending their forests.

The Global Alliance of Territorial Communities represents communities who call the world’s largest tracts of forest home, from Mesoamerica to the Amazon and Indonesia. Together, they are proving to the world that protecting Indigenous and community land rights is essential to mitigating climate change.

A few hours later, to the sound of drums and rattles and the smell of burning sage, the Indigenous activists converged at the river’s edge, the Eiffel Tower looming behind them, to memorialize the moment in a photo. Wielding a wooden paddle passed across continents, Mezua, flanked by a Native American chief in feathered headdress, explained that their Indigenous communities together manage half the world’s land but have legally recognized ownership of just ten percent. Ensuring these communities have secure land rights can reduce deforestation and prevent billions of tons of carbon from escaping into the atmosphere every year. (If tropical deforestation were a country, it would trail only China and the US in annual emissions.) A few days later, it was announced that Indigenous rights were to be included in the final Paris Agreement. In response, the alliance presented its paddle to Christiana Figueres, executive secretary of the Convention, as a way to mark their victory.

It had been a long time in the making

Though tropical-forest countries have been home to Indigenous peoples’ movements for decades, when the UN adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, there were few unified forest-community international networks in existence. A few years later, in the months leading up to the 2010 COP, a dozen or so groups in Mexico and Nicaragua got together to highlight their region’s many successful Indigenous- and community-managed forest schemes.

In terms of global emissions, Levi Sucre Romero, a BriBri from Costa Rica and leader from the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB), knew that protecting Mesoamerica’s forests was only one part of the solution. To have a wider impact, he and his colleagues realized they would need to build partnerships with communities who call the world’s largest tracts of forest home. Sucre, Mezua, and AMPB connected with the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA) and began forging ties with Indonesia’s Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), representing 17 million forest-dwellers. The collective then allied itself with APIB, the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, the main network representing the movement there, and later with the Network of Indigenous and Local Populations for the Sustainable Management of Central Africa Forests. Collectively, members of the alliance protect 840 million hectares of land and forest—an area larger than the contiguous United States—but 400 million hectares are yet to be recognized by governments as community land.

Indigenous lawyer Dinamam Tuxá of APIB advocates for the rights of his communities who face violence amidst rollbacks of environmental protections and the rise of anti-Indigenous sentiments in Brazil.

Mina Setra, a Dayak leader from AMAN, has watched the forests of her Indonesian homeland be replaced by oil-palm plantations. She represents 17 million forest communities at global policy arenas.

AMPB’s Levi Sucre Romero, a BriBri from Costa Rica, says the forests of Mexico and Central America are only one part of the solution. He connected with AMAN, APIB, COICA, and others to help build the alliance.

Though Indigenous communities are scattered across the world, they share many of the same challenges. Rising sea levels, droughts, forest fires, and flooding are already laying siege to their homelands. At the same time, their forests are being decimated, their lands grabbed, and their people murdered at the hands of logging, hydroelectric, mining, and agricultural interests. The London-based watchdog Global Witness recently reported that an average of four land defenders and environmental activists are killed every week, more than a third of them from Indigenous communities.

By September 2014, when the New York Declaration on Forests was announced at the UN Climate Summit, the alliance was ready to present itself on the world stage, joining 200-plus national governments, multinational companies, and financial institutions to make a voluntary pledge to steward the forests they manage. While in New York, they held workshops to brainstorm advocacy strategies leading up to the COP scheduled for that December in Lima, and then they spent two weeks in the Peruvian capital building the sorts of international bonds you can’t get from email exchanges. That camaraderie didn’t happen overnight. Some of the organizations, for instance, harbored a mutual suspicion from the get-go. Sucre Romero recalled one “very low point” when the group was trying to agree on a set of key themes and arguing over the wording for one of them. Well, they were trying to argue. With Portuguese, Bahasa Indonesia, and Spanish flying around, communication wasn’t always easy. “We learned that we needed to speak from an emotional point of view,” said Sucre Romero, “more than focusing on what a specific word in whatever language could convey.”

In 2014, AMPB’s Candido Mezua and Norway’s then–Minister of Climate and Environment, Tine Sundtoft, called for the inclusion of Indigenous rights in climate negotiations during the UN COP20 conference in Lima, Peru.

When they headed back home to their separate countries and continents, the members continued to plot their next steps from afar. They emailed regularly and occasionally arranged for site visits and youth exchanges to learn more about one another and continue to build trust. With support from the Ford Foundation and the Climate and Land Use Alliance, they began gathering annually for intensive planning meetings, establishing a careful hierarchy of communication. They also partnered regularly with outside researchers, scientists, and storytellers, while remaining vigilant about running the show themselves.

“What is most important is that we have a direct connection with the communities,” said Mina Setra, a Dayak leader from AMAN who has watched the forests of her Indonesian homeland be replaced by oil-palm plantations. “We are not non-governmental organizations. We are a people’s organization,” with roots in the forest.

In the run-up to the Paris meeting, the members of the alliance honed a concise narrative, improved their digital and social-media skills, and identified a set of key demands. They wanted the world to recognize and enforce their territorial rights and stop the criminalization and murder of forest guardians. In addition, they sought direct access to financing for climate-mitigation measures; the right to have a say over investment projects that affect their cultures, traditions, and lands (what’s known as the right to “free, prior, and informed consent”); and the incorporation of traditional knowledge in solutions developed to fight climate change. The consensus on messaging marked a significant milestone. “Years ago,” said COICA’s Tuntiak Katan, an Ecuadorian who now serves as one of the alliance’s leaders, “we could not think of coordinating closely with other Indigenous communities to advocate for our people like we are currently. This is something that is only going to continue to grow.”

Using computer software, cell phones, GPS systems, and drones, the alliance has mapped their territories to demonstrate how community-managed forests prevent deforestation and keep carbon from being released into the atmosphere.

When the time came for COP21, the alliance demonstrated for the gathered powerbrokers the work they do back home, from creating detailed maps of traditional lands to employing drones, sophisticated computer software, cell phones, and GPS systems to monitor their forests for illegal activity. The references in the final Paris Agreement to both traditional knowledge and the notion of free, prior, and informed consent served as proof of just how far they had come. “This was compared to 2007,” Setra said, “when there was nothing, except that we were included in a category of ‘vulnerable people.’”

By 2017, the alliance had become even more emboldened and ambitious, with over 30 of its members boarding a luxury coach tricked out like a rock-and-roll tour bus to travel across seven European cities and claim seats at the table with lawmakers and environmental ministers. If Not Us Then Who?, a storytelling and events support organization and a longtime partner of the alliance, organized events around the bus tour and documented it in a series of vlogs. In Berlin, they demonstrated before the Brandenburg Gate as TV cameras rolled, and in London, they marched solemnly across Parliament Square bearing photos of fallen land defenders, steadily building their case that the international community must take a stand to ensure that their territories be recognized and their human rights protected.

Over time, they’ve felt their power as a group grow, just as communications among them have found a more natural groove. “One of the nicest things we’ve experienced,” said Sucre Romero, “is when we’ve been at an event like COP and our expositions flow from one another as if we had always been together. I would be speaking about something, then Mina would come in in a different language and we would harmonize. People would be like, ‘Wow, they really live together.’”

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

The groups have become a consolidated body on their public advocacy efforts, joining forces at press conferences, sharing each other’s stories, promoting one another’s campaigns—and reporting on the all-too-frequent occurrences of murders among their communities. And they’ve become increasingly sophisticated about how to leverage their communal power back home. In Brazil, for instance, as President Jair Bolsonaro implemented anti-Indigenous policies and rolled back environmental and social rights, Dinamam Tuxá, an Indigenous lawyer from APIB, said that he and his colleagues looked to their international brothers and sisters for help. “The Global Alliance has raised our ability to advocate for ourselves at a level we could never have done alone.”

Similarly, alliance members are learning to convince their compatriots of Indigenous groups’ relevance on the national level, pointing to the benefits of their work in protecting biodiversity and endangered species and in reducing the risk of emerging diseases and pandemics. During the early months of COVID-19, the communities united under Indonesia’s AMAN locked down their villages and managed not only to stay healthy but to also produce so much rice they were able to send surplus tons to the thousands in need in Jakarta. They’ve also begun to emphasize the role of forest economies in providing employment and social protection for those living in rural areas, offering evidence, for example, that cutting down forests can change the way water cycles through the environment. By opening new areas for agriculture, in other words, governments may end up interrupting the very rainfall patterns they rely upon for successful harvests.

Claudette Labonte, a leader of the Palikut people of French Guiana, marched during the 2018 San Francisco Climate Summit. She coordinates COICA’s women and family program across the Amazon River Basin.

COICA’s Tuntiak Katan has recently traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with members of the Biden administration and inform Elon Musk that forest communities already have the best technology for carbon capture.

Over time, their self-perception has also evolved. In September of 2018, during the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco, If Not Us Then Who? partnered with a local artist to organize a guerilla action involving the projection of 50-foot-tall images of alliance leaders on buildings around the city. “When their faces came up, they got very emotional,” said Paul Redman, the founder of If Not Us and whose board of trustees includes AMAN’s Setra and COICA’s Michael McGarrell. “There were invariably tears.” Up there in their traditional clothing, set dramatically against a black background, each of them took on the persona of a superhero.

The event came on the heels of a camping trip along the Klamath River, in Northern California, hosted by the Yurok people, one of the few Indigenous groups still protecting their ancestral forest territory in the US. By day, the visitors from the alliance toured the native lands and exchanged traditional practices around forest-fire management, while evenings were spent gathered around the fire to share songs and community-based solutions that had proven successful in their homes. The exchanges led them all to appreciate the strength of their stories, while fortifying them for future audiences with climate negotiators and CEOs.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

“Projecting images of the leaders on San Francisco’s skyline,” said AMPB’s Sucre Romero, “carrying an Amazon canoe all the way to Paris, taking over Times Square with our messaging—it’s a way of bringing our stories to places where people don’t know them.” Those messages take on particular force, added Tuxá, who often appears in traditional face paint and headdress, “because there’s no intermediary. It’s the people experiencing the violence who are speaking out about it.” At the same time, said Sucre Romero, “being on the Hudson,”—the group had canoed through New York to celebrate the signing of the Paris Agreement there, “had relieved some of the stress and the heaviness of the city. The voice of the river, the singing of the leaves,” he said, “it felt a bit like home.”

Among the greatest benefits of the alliance, Setra said, is that members now find themselves seated among those politicians, donors, CEOs, and other decision-makers, so they influence policy and advise businesses on how to clean up their acts. COICA’s Katan has sat across the dais from Bill Gates and recently traveled to Washington, DC, to meet with members of the Biden administration and inform Elon Musk that they already have the best technology for carbon capture.

That’s a far cry from the way things used to be. “Ten or 15 years ago,” said AMPB’s Sucre Romero, “we would talk about traditional knowledge and how we needed to protect the forest, and they would say, ‘Oh, that’s really nice. That’s really interesting, what the Indigenous peoples are saying. Let’s take a picture.’ Then when we would get back to our countries and they wouldn’t listen to us.” He and his colleagues in the alliance joke that “it was easier to sit down with national environment ministers in France than it was to sit with them in our own countries.”

Another victory

The alliance celebrated another victory in 2019, when the UN released a Special Report on Climate Change and Land, endorsed by governments worldwide, declaring that “land titling and recognition programs, particularly those that authorize and respect Indigenous and communal tenure, can lead to improved management of forests, including for carbon storage.” It also identified empowering Indigenous peoples and enhancing local community collective action as two of the most important steps to enable sustainable land management for climate mitigation.

The acknowledgement reflected a broader reframing of the public narrative, from one that depicts Indigenous peoples as poor, marginalized populations who destroy forests and siphon resources from the state to one that recognizes them as masters of community-based solutions grounded in nature and skilled at employing the latest scientific data and tools to effectively manage their forests—and as people whose efforts benefit those living far beyond the borders of their territories.

The work, however, is far from over. Countries like Indonesia and Brazil have passed increasingly restrictive regulations on Indigenous peoples to protest against their governments. The impacts of climate change are intensifying, with heatwaves and other extreme weather more frequent than ever, while COVID continues to impact Indigenous communities harder than others.

With the impact of climate change intensifying and COVID-19 raging, the work of the alliance is more urgent than ever. Leaders of the alliance plan to raise issues facing their communities to policymakers in Glasgow, Scotland, during COP26, in November.

At the same time, the Global Alliance is increasingly well-positioned to build partnerships with social justice movements worldwide. Just as Indigenous peoples are left out of decision-making processes and criminalized and murdered for defending their land and rights, communities of color in the United States and elsewhere have suffered similar marginalization. The “Our Village” pop-up space, organized annually with the alliance by If Not Us Then Who? at global action sites, was coordinated with the Hip Hop Caucus at the San Francisco Climate Summit. It’s event series focused not just on climate change but on injustice and inequality more broadly, gathering Indigenous peoples, communities of color, and grassroots voices to support a range of locally driven actions. The alliance teamed up with three social media influencers—Victoria Volkova, a trans woman from Mexico; Jouelzy, an African American; and Murilo Araujo, a queer Afro-Brazilian—to amplify its role as a climate solution to more than two million followers on Youtube and Instagram. And last year, astronaut Jessica Meir joined the alliance in sending a unified message—from space to cities and forests—about the importance of protecting the planet.

Four land defenders and environmental activists are killed every week. Gathered in New York, the alliance responded to the murder of Berta Cáceres, a leading environmental defender of the Lenca people in Honduras, with #IAmBertaCáceres.

Forest communities at COP26

Looking ahead to November’s COP26, in Glasgow, where the alliance plans to meet with John Kerry, President Biden’s Special Envoy for Climate, the leaders are working to secure funding for community-forest protection—while keeping their expectations in check. “Every year we go to COP and there are several commitments from governments and conservation organizations,” said Katan, “but we’re always left with commitments that aren’t implemented in our territories.” He cited a recent report that found that less than 1 percent of climate finance supports Indigenous and local community tenure security and forest management—only $270 million per year. “We want to propose a mechanism for allowing climate finance to reach our communities,” Katan said.

With countries beginning to emerge from COVID and governments across the Global South under pressure to jumpstart their economies—likely at the cost of exploited natural resources—time is of the essence. While transitioning to renewable energy will involve building massive infrastructure and transforming an entire system of economic relationships, the members of the alliance have demonstrated that they know how to mitigate climate change by protecting forests in a way that is both low-cost and effective. Were they to be provided with financial and political support, they could scale up their efforts immediately. In the meantime, they’ll continue to shift the broader narrative. “We’re going through the lands of the colonizers,” said Patricia Juruna, an Indigenous youth from APIB. “We are traveling the paths that were previously denied to us.”