Land ownership has been a contentious issue in Jakarta, in particular around the resettlement of communities in Kampung Pulo on the eastern side of the city. Kampung Pulo is 8.575 hectares and inhabited by around 5,000 families, most of them low income. They are made further vulnerable by the location: The whole area is prone to seasonal flooding, and the current homes are not built to accommodate those floods.

To solve this problem, Jakarta’s governor has been negotiating the resettlement of the Ciliwung riverside communities of Kampung Pulo. Ciliwung Merdeka (Free Ciliwung), a foundation grantee, has been working with the government and communities to ensure that residents of these low-income communities are empowered to participate in the spatial planning of their residential areas.

The foundation’s Indonesia office has worked with Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama in the past, providing technical assistance to help the Jakarta city government implement an open data policy and improve public access to government information. The governor is a well-known anti-corruption champion, and he has done much to advance transparency within the government. He is now facing the challenge of embracing a vision of a fully inclusive city, where all people, regardless of class, ethnicity, or gender, have access to the same opportunities.

Recently the relationship between Ciliwung Merdeka and Jakarta’s governor swung from collaboration to confrontation. Towards the end of August 2015, the governor ordered the forced eviction of houses that were built right on the side of the river. Some middle-class Jakartans supported the governor’s actions but others would like to see him use participatory negotiation rather than force. The media and political networks played important roles in influencing the parties’ decision to return to the negotiation table. On September 18, the governor officially declared his support for Ciliwung Merdeka’s redevelopment plan.

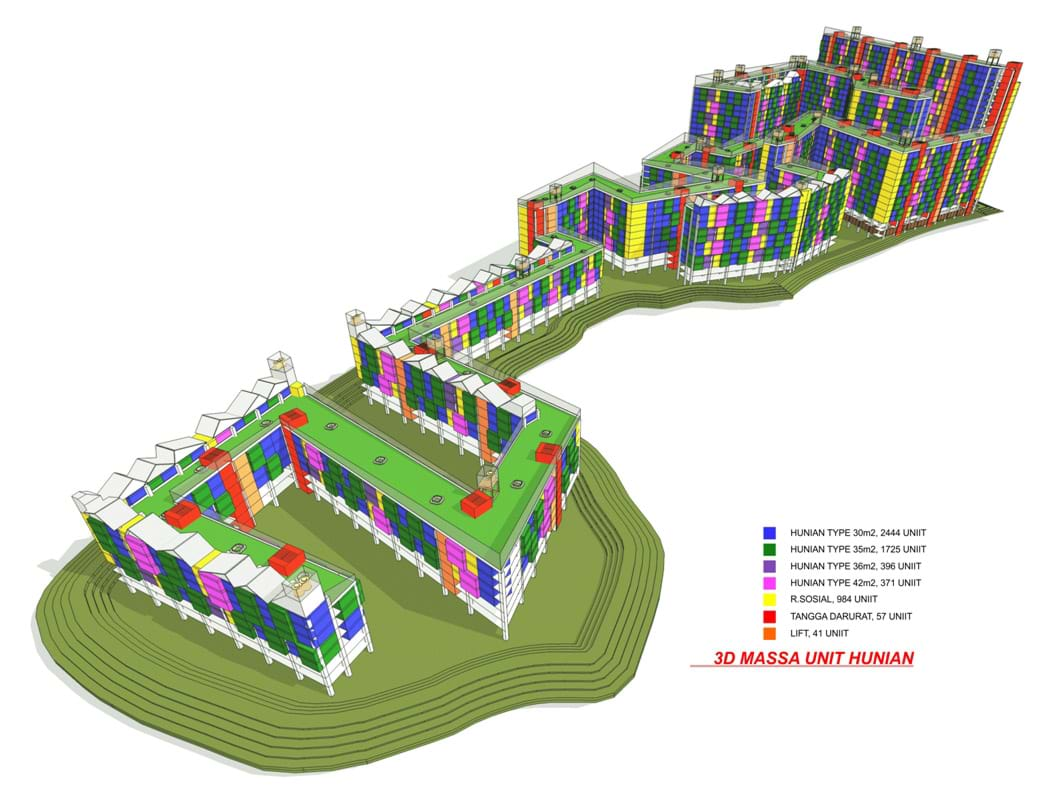

The plan was drafted by our grantee with assistance from progressive architects and engineers and in consultation with the communities themselves, and it aims to accommodate all 5,000 families in 5,000 apartment units. The government has made an offer to provide residents with a replacement for their current homes that amounts to 150 percent of their original square meter space, assuming they have official certificates for their land. The design produced by Ciliwung Merdeka and its partners is aimed at developing apartment buildings that are able to accommodate seasonal flooding, while also allocating 30 percent of the area for green open spaces, and providing room for community members to support their livelihoods. These spaces could be used for repair shops, eateries, workshops to produce small-scale processed foods, phone card booths, and coffees shops. There will also be a traditional market separate from the housing units where people can buy and sell agricultural products, fish, poultry, and meat. It is estimated that the total cost of the area development would come to three trillion rupiah (around $215 million).

In early October, Ciliwung Merdeka met with Jakarta’s Housing Agency to agree on how to implement the redevelopment plan. Ciliwung Merdeka will play the role of mediator between the people of Kampung Pulo and the Jakarta government, facilitating the participation of the communities in the land-for-housing swap. Ciliwung Merdeka and its partners now face an enormous facilitation challenge. They will need to facilitate the resettlement of around 5,000 families in a community where the issue of land ownership and control remains extremely contentious. The governor, Ciliwung Merdeka, its partners, and members of the Kampung Pulo communities have agreed to work together to transform the area into a vibrant cultural and culinary center that can become the soul of Jakarta. However, developers are competing to get a slice of the pie and some community members stand to benefit in those deals—adding to the sources of discontent among the people of Kampung Pulo.