Featured Artists

Art is advocacy. Art is healing. Art is universal.

For artists, art is a solution—a manifestation of emotion and realism, a salve for hardship and a call to action.

The Middle East and North Africa is a tapestry of cultures, languages, religions and humanity. The world often hears about this region when there’s a tear in the tapestry, rather than when artists add an extra layer of detail to enrich its beauty and character.

Inevitably, the region’s complexity, conflicts and challenges are present in the work of its many artists. From Tunisia to Lebanon, artists have always been a voice for the people, a source of resistance against the status quo. They unpack and lay bare both the joy and suffering to be found in the twists they navigate, turning it all into inspiration.

Today, the challenges facing artists there are many—enduring inequalities more than 10 years after the Arab uprisings began, COVID-19 bringing the arts to a standstill, the explosion in Lebanon and more. At the Ford Foundation, we believe it is critical to support arts and culture in the Middle East and North Africa to enrich civic space, maintain freedom of expression, encourage diversity and foster creativity in society. Artists possess the unique gift of poetic expression—a service that helps society at large process hardship and crisis, heal and renew. Through their crafts, artists build shared understanding, bridge divides among different communities and offer hope to the public. And yet, artists often work in precarious working conditions and relationships without access to social protections and financial assistance afforded to other professions.

While some countries, such as in Europe, have explicitly extended relief, stimulus and recovery packages to artists and technicians in the arts; this is not yet the case in the Middle East and North Africa. Since 2020, we have been supporting two new initiatives, Art Lives and the Lebanon Solidarity Fund, that provide emergency funding to artists during COVID-19 and after the explosion in Beirut. Our partners on these initiatives, such as Culture Resource, Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, Ettijahat-Independent Culture, Action for Hope and Mophradat have long supported artists across the region. We work with them to support vulnerable artists whose livelihoods came to a grinding halt in the last year. Other organizations, such as L’art Rue in Tunisia, offer residencies to artists at a time when other sources of income dried up.

Meet six artists we support through and with our partners. For them, art is a lifeline. Each one adds their unique story to the fabric that brings the tapestry of the Middle East and North Africa to life, animating the shared struggle for a more just and equal tomorrow.

Bound by no borders: Khawla Ibraheem, Golan Heights

Khawla Ibraheem is a Syrian actress and playwright living in the Golan Heights—land controlled by Israel since the 1967 war with Syria. Her identity is caught between the Syrian civil war, her refusal of Israeli citizenship and her work in the West Bank in Palestinian theaters. She puts this crisis of borders into her work, writing on themes of identity and belonging.

Khawla Ibraheem is of Syrian descent, but when she is asked where she’s from, the answer is never easy—the land she grew up on is disputed. She was born and raised in the Golan Heights, an area under Israeli control since the 1967 Six-Day War with Syria. Israel annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, but most, including Ibraheem, still consider it occupied. She and most of its Syrian residents continue to refuse Israeli citizenship. When the war in Syria intensified in 2012, the promise of returning to Syria faded, pushing the identity of many in the Syrian community in the Golan Heights—and of Ibraheem—deeper into limbo.

So, how does Ibraheem navigate the complexity of her identity and reconcile with what home means? Make art. As an actress, director and playwright, Ibraheem’s work dramatizes the toll of being caught in a conflict that does not have a clear solution.

“Art is the only way to feel I belong and theater is the only place I feel at home,” Ibraheem said. This is what motivated her to move from acting to writing and directing. “With all of the complexity around me, I wanted to be able to tell my story on my own terms.”

Her first play, Borders, depicted a Syrian girl trying to cross the closed border into the Golan Heights. Though she has roots on both sides of the border, she is unsure where she belongs. “She was longing for a place she never saw,” Ibraheem said. “But then once she makes it over, she’s longing for a place she knows. She realizes there will always be longing, on either side.”

While Ibraheem is able to work in Israel, she feels constrained by the political situation. She senses a kinship with the Palestinain community in the West Bank and prefers to work there, producing her work in Jenin and Ramallah. But even that weighed on her because while Ibraheem can freely cross through checkpoints her fellow thespians cannot.

Ibraheem hopes her work can frame the land as sovereign with people as its stewards, not with artificial borders that stem from human conflict—an artistic and emotional way to respond to the crisis.

“I stopped thinking about political solutions long ago,” she said. “I focus on art and telling a good story. That is my solution.”

The beauty of disfigurement: Mohamad Khayata, Lebanon

When Mohamad Khayata was working on his master’s degree in fine art in Damascus, Syria, he booked a show of his work in Lebanon. He arrived in Beirut with a small suitcase expecting to stay just a few days.

While there, worsening, violent conditions at home made it likely he’d have to leave school and serve in the Syrian military if he returned. “My father told me, ‘you’d better not come home,’” Khayata said. Nearly 10 years later, he has yet to return to Syria.

Alone in a new city with nothing but the clothes he brought, Khayata had no choice but to build a new life in Beirut. He started with his art. As a Syrian refugee, his legal employment options were limited, and most work had to be done off the books—including art.

“My art is explaining the life of refugees living in Lebanon,” said Khayata. “I am a part of those people. I’m a mirror. I have to reflect back all the difficulties that they face.”

His work struck a chord and he started to exhibit amidst the local art scene. But exhibiting art is not an approved occupation for refugees and can result in fines or denial of a residency permit. He often does not attend exhibitions and keeps his name off of local posters.

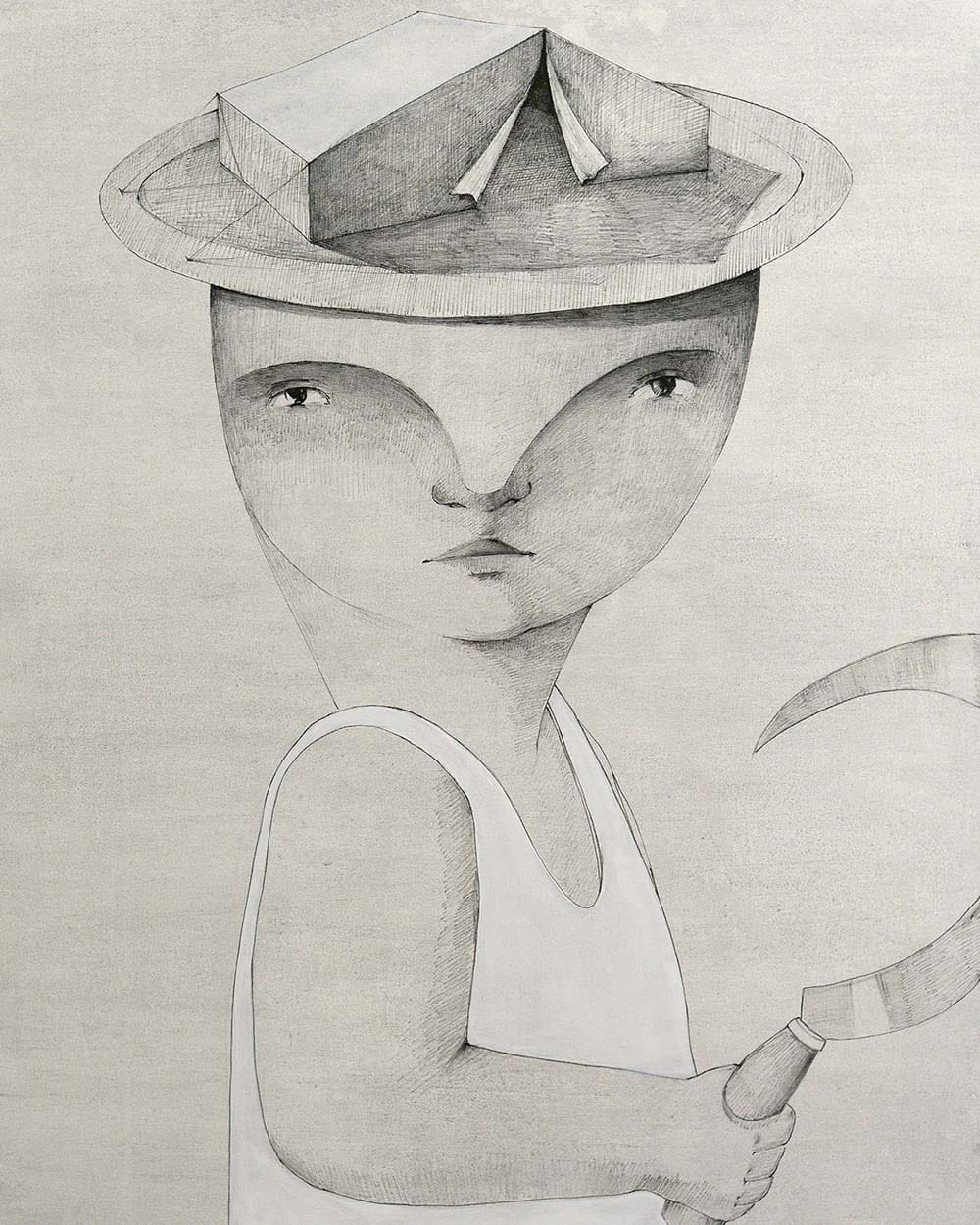

Mohamad Kahyata, a Syrian refugee in Lebanon, creates characters with distorted proportions. Seen here with his artwork, he aims to portray the refugee experience through the beauty present in disfigurement.

But this hasn’t stopped his work from gaining international recognition and gracing galleries across the United States and Europe. He brings the experience of displacement to life through his signature style of disproportionated characters, which embody the distorted realities of refugees.

He had hit his stride just as COVID-19 shut down galleries around the world, and then, the Beirut explosion, which took place a quarter mile from his home, damaged all of his work. As a Syrian, it was hard for Khayata to find financial aid to carry him through these twin disasters. Once again, he found refuge in the art community. Action for Hope helped rebuild his studio so he could get back to creating and exhibiting, recently showing new work in Cairo and Los Angeles.

Though he’s rebuilt his life in Beirut, he misses the home he left in Syria. But now with the passing of both of his parents and the country’s civil war intensifying, he knows the home he misses is no more.

“It’s a hard time for everyone here in Beirut and in Syria,” he said. “But I know I’m lucky I am still alive. I am working, making art—that’s what my parents would want. I am happy.”

The drama of displacement: Radwan Taleb, Iraq

Radwan Taleb spent 15 years bringing characters to life in Syria as a theater actor, writer and director. But in 2014, the drama off stage became untenable. As conditions in Syria grew dangerous and dire, Radwan and his wife, Atyaf Mahdi, fled to Iraq, where they traded in the richness of theater life for administrative jobs.

Yet Taleb never lost sight of his passion for performance. He and Mahdi chose to settle in Sulaymaniyah, a city in the northern Kurdistan region of Iraq, because it’s known for its cultural history. There, Taleb helped create The Sabunkaran Theatre Group, a small, amateur troupe hosted in a monastery. After three years, theater was finally back in his life.

The Sabunkaran Theater Group in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, is a theatrical home for people regardless of their cultural background and the language they speak, including many refugees and internally displaced people. Radwan Taleb, a Syrian refugee, co-founded the troupe and directs many of the plays.

He and Mahdi, an actress and dramaturg, brought their expertise to the troupe. When Taleb became the director, he worked to bring it from amateur to professional. But he faced a constant stream of challenges: some actors spoke Arabic, others Kurdish, all had to juggle full-time work, and just as a production would come together, some actors, many displaced themselves, would leave to migrate to Europe when an opportunity arose. Despite the instability, Taleb led the troupe to several productions, ranging from a play based on a 2500-year-old Greek farce by Aristophanes to a Samuel Beckett piece. He even organized the troupe’s first performances at international venues, which were postponed because of the pandemic.

With all his efforts to professionalize the troupe, Taleb is intent on keeping it as a resource for the community in Sulaymaniyah. It’s the escape and sense of purpose he has to offer for people caught in the cross hairs of conflict.

“What’s most important is that the actors feel they are doing something meaningful here, as refugees and people who are displaced,” Taleb said. “When we perform in camps, we discover entire communities who were never exposed to theater before. Us performing there brings them some joy–and there’s always someone who wants to get involved.”

Lifting up the homeland: Drifa Mezenner, Algeria

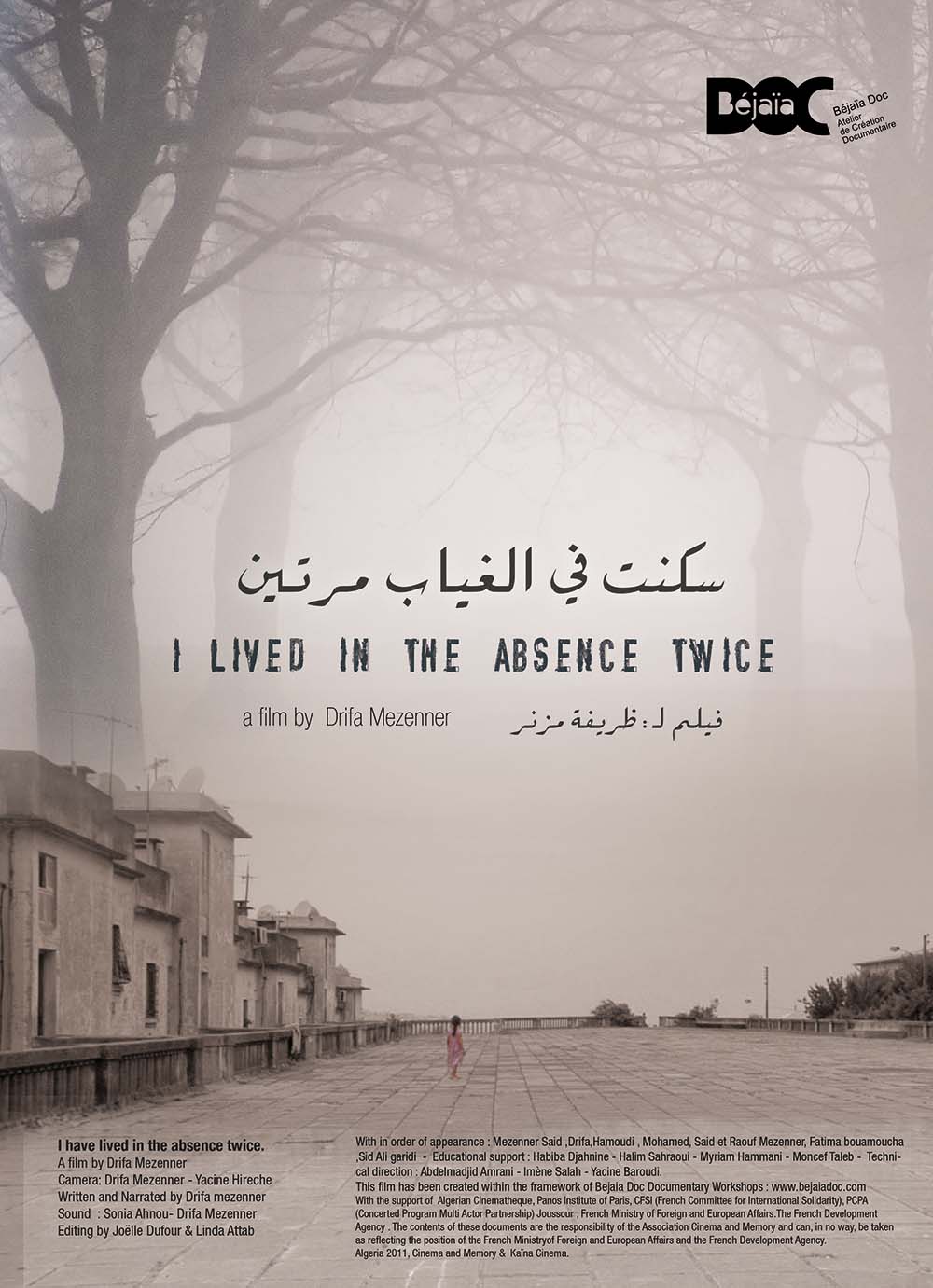

In the opening scene of Drifa Mezenner’s short film, I Lived in the Absence Twice, she asks her father some tough questions. Are conditions in Algeria better than they were in the Dark Decade, during the country’s civil war that started in 1992? The question, and the film, come in 2011, amid the dawn of the Arab Spring.

Algerian Filmmaker Drifa Mezenner looks at the toll years of war have taken on families in her home country. Most families have at least one member who has fled the country. In I Lived in the Absence Twice, seen here, she deals with the effects of her own brother leaving and never coming back. She’s now launched a platform to connect Algerian filmmakers with producers, Tahya Cinema.

In the film, her father, too angry about the past to address the question, focuses instead on his son and Drifa’s brother, Sofiane, who fled to England when the Dark Decade began. He was 19. Her father insists that Sofiane will eventually come home, but Mezenner knows he won’t. Countless Algerian families have a family member who fled to safety—like her brother—and never came back.

For Mezenner, filmmaking is a way to document the cultural and emotional effects of war and the rise and fall of hope.

“I was trying to tell the story of the country through my family,” she said. “The main focus for me is always to be a witness to what’s going on in Algeria and to better understand it.”

Drifa Mezenner’s short film, I lived in the Absence Twice, explores the impact of people fleeing the country on families, including her own.

Her commitment to storytelling always came up against a lack of support for filmmakers in Algeria—especially women. She refused to accept this. “I needed a solution not just for me, but for every filmmaker, especially the new young talents,” she said.

In 2018, she put her own filmmaking on the back burner to build a platform, Tahya Cinema (Tahya means “long live”) to mentor young filmmakers and connect them with producers. Since the platform launched in 2021, she has attracted a roster of artists, but is working to find more producers and funders—a challenge in a modest funding landscape

But she hasn’t stopped bearing witness through her films, including the latest wave of Hirak protests, an anti-corruption movement that has been making waves in the streets of Algeria for the last two years. It keeps her motivated to make Tahya Cinema succeed in lifting up the stories of Algeria.

“I see the change we are aspiring to and how we want to live, the freedom, the education,” she said, citing some factors that led her brother to flee and still fuel the protests. “For me, this work on Tahya, this moment is the answer I am looking for.”

No progress without art: Ridha Tlili, Tunisia

The Arab Spring is widely said to have started in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, a small town of less than 50,000 people, miles from the capital of Tunis. An act of protest there begat waves of demonstrations across the region and disruptions in government that continue to ripple over 10 years later.

Sidi Bouzid is filmmaker Ridha Tlili’s hometown; he had a front-row seat to the spark that lit the fire. Yet, he chose not to make films about protests in the street, but to capture the cultural current of freedom and optimism where it all began. His first film after the start of the Arab Spring was about graffiti, as street artists decorated public walls in Sidi Bouzaid with symbols of protest and hope.

However, as the political situation in Tunisia continually shifted in the ensuing decade, Tlili found himself portraying the toll of it on his fellow citizens with Thirsty Tunisians, a documentary about the water scarcity crisis in Tunisia. Yet he focused much of his work on other artists—poets, folk musicians and singers—who, like him, were both experiencing the toll of the revolution and telling its story, often without adequate support.

The Arab Spring began in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia—the hometown of filmmaker Ridha Tlili.

He documented the many-faceted effects of the ensuing years on Tunisians.

Tlili’s first film after the revolution captured the graffiti that sprung up around Sidi Bouzid with symbols of hope and protest.

Tlili has documented Tunisia’s struggles but also its joys, such as its burgeoning break dance scene.

“The people in my films, it’s my way of giving them power,” Tlili said. “They are the ones telling the story of the revolution.”

Tlili’s prolific quest to tell his country’s story came to a sudden halt with COVID-19. Not only did safety concerns preclude filming, funds for arts and culture dried up, with most redirected toward public health measures—a seeming necessity to some, a measure of censorship to others. As secretary of the Tunisian filmmaking association, he has advocated for artists to have more support and opportunity during the pandemic.

“We don’t have progress on anything if we don’t have a place for artists in society,” he said.

After months without working, Tlili began a residency with L’Art Rue. It commissioned a film on the emerging breakdance culture in Sidi Bouzid and across Tunisia. He frames his five subjects and their gravity-defying prowess as a metaphor for the resilience of Tunisians in the last decade—a source of inspiration to keep hope alive that the promise of the revolution will be realized.

“Breakdancers learn how to fall and how to stand up again, to go on and never give up,” said Tlili. “It’s like finding a new solution every time they’re down. How will they get up this time?”

Transcending his surroundings: Bassem Yousri, Egypt

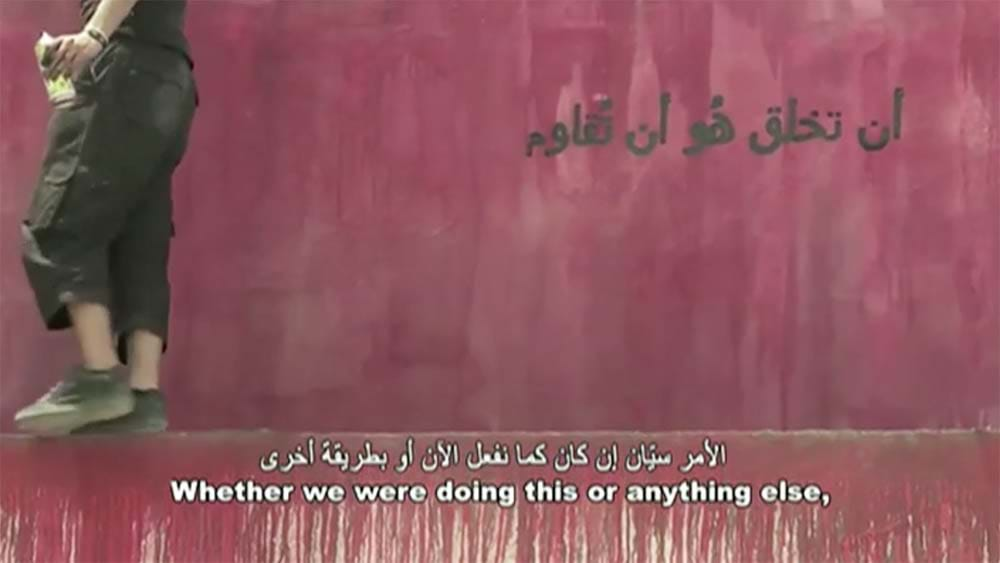

In his 2012 work, It’s Not As Easy As It May Have Seemed To Be!, Egyptian artist Bassem Yousri portrays the power of the masses, depicting hundreds of figures climbing up walls and knocking down columns as they take over a gallery space.

It was a direct reaction to the Arab Spring he was living through in Cairo. But when the revolution settled into the banality of governance, he and his work also evolved.

His 2020 piece, Where Do We Go From Here?, portrayed the clutter and disorder seen on and around the public facades of Cairo, including government buildings. Yousri wanted to investigate the relationship between this visual representation of authority and its effects on daily life, using a more subtle approach that looks beneath the surface.

The shift in his work was influenced by the political situation, but also a sign of his personal evolution.

“I grew up and matured, and I think my reflections are deeper now than when they were responding directly to political events,” he said. “I am looking at the heart and soul more than the events. You won’t find what’s in the newspapers in my work.”

Egyptian Bassem Yousri’s art has shifted in tone over the years. Above is a piece from a work he created 10 years after the Arab Spring, which looks at the clutter in public spaces in Cairo and its relationship to authority. The measured feel of this is in stark contrast to the work below at the start of the revolution, which depicts hundreds of figures knocking down columns and climbing walls.

When his work started gaining traction beyond Egypt, he found that he had to push back against the idea that his art is limited to the experience of his country’s politics.

In a 2020 essay, Yousri recounts giving a talk in New York City in 2016 and being asked if, as an artist, he was addicted to conflict. The question astonished him because it assumed that conflict was the sum of his experience as an Egyptian, or that political struggle is only something that affects people in the Global South. Yet artists everywhere have to grapple with struggle—it’s a shared, universal experience.

“People in the USA or Europe are free, but are still fighting for progress on so many different issues,” he said. “All over the world, we never stop asking for better social conditions, and artists everywhere never stop telling that story.”

Ford’s work on arts, culture and media in the Middle East was spearheaded by Laila Hourani, a Ford Senior Program Officer based in Cairo, Egypt. Over a period of eight years, Hourani designed a robust program strategy and cultivated partnerships with civil society funders, artists and activists alike.