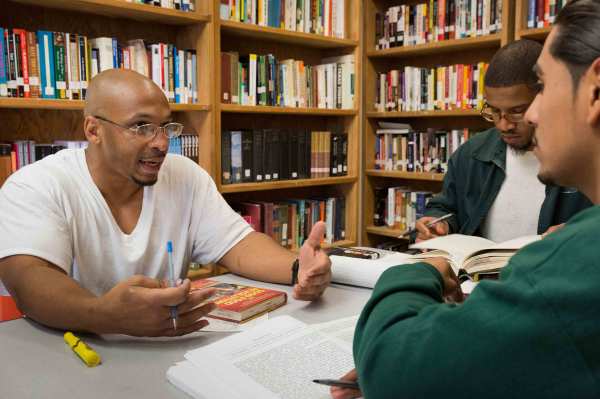

In late 2015, Darren Walker approached the foundation’s Talent and Human Resources team and asked us to create a professional development program for graduates of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). At the foundation, we’ve long supported the innovative work of BPI, which gives incarcerated men and women an opportunity to earn a Bard College degree while serving their sentences. And we’ve highlighted our commitment to this program, how it transforms the daily realities of incarcerated people and offers them a sense of possibility that is essential to rebuilding their lives and participating in their communities after their release from prison.

The foundation’s work with BPI also aligns with our support for fair-chance hiring policies and other efforts to eliminate barriers to employment for people with conviction records. In short, we don’t believe a prior history of convictions should disqualify people from employment—especially since this is a problem that disproportionately affects people of color, whose lives have been hit hard by decades of overcriminalization.

So when Darren approached us with the idea, we were as eager as he was to figure out how we could “walk our talk” on these issues.

Listen to the NPR story featuring BPI graduate and Ford Foundation employee Lavar Gibson:

The first steps: Listening and learning

As a social justice foundation, we had the advantage of in-house expertise on prison education and re-entry issues. But our human resources team had limited experience working purposefully with formerly incarcerated people who were re-entering the workforce. We had a clear goal—to deliver a program that built the BPI graduates’ skills and knowledge and prepared them for jobs that would lead to a career. But we also had lots of questions.

So we started by talking to the experts: members of our staff who work on employment, education, incarceration, and racial justice. In turn, they connected us to leaders from organizations they support, including JustLeadershipUSA, the College and Community Fellowship, A New Way of Life, and the Vera Institute of Justice. Experts from those organizations generously shared their insights into how we might structure our program and maximize its benefits for everyone involved. And, of course, we also relied on the knowledge and expertise of BPI co-founder and executive director Max Kenner. Jed Tucker, BPI’s director of re-entry, was also a key partner in this effort.

To figure out the nuts and bolts of the program, Max and Jed helped us organize a focus group with several BPI graduates, who gave us candid input about what they would personally find most useful in a professional development program. Their contributions were invaluable: Hearing directly from these graduates made us feel more comfortable designing a program that could serve their needs as they saw them, while also taking into account the things we and our partners knew would prepare them for what came after their experience at Ford. Input from experts helped us make other practical decisions, like the one to subsidize participants’ commuting costs for their first three months of work—giving them a financial cushion as they were adjusting to a new situation, while keeping our assistance within the bounds of real-world expectations. That balance, we learned, was an important one to strike.

A program takes shape

In many ways, the program we designed is similar to the summer internship program we’ve run for college students for decades. The BPI program is longer and more intensive, with additional supports, but the ethic for both was the same: Take promising people early in their careers and expose them to social justice efforts and workplace norms. In keeping with that ethic, both programs are paid employment, at living wage rates (above minimum wage), with requisite benefits. From the beginning, we knew we wanted the BPI program to span a full year—the three months of our traditional summer internship program simply wouldn’t do enough to advance the career of someone with limited professional experience.

Ultimately, we decided to offer the interns two tracks: Those who were specifically interested in a career in IT, finance, communications, or human resources were able to spend a full year working in those departments. For those who were interested in exploring a variety of career paths, we offered a rotation program that involved spending three months in four different departments over the course of the year. We tried to keep the program flexible; if interns found that the learning opportunity in a particular area of work was beneficial, we allowed them to extend their time there.

It was important to us to make a serious investment in the graduates’ learning and success, and we recognized early on that doing so requires a real commitment on the part of any managers involved. So it was crucial to have enthusiastic support across the foundation. In addition to working full time, we built in structured professional development opportunities, including certifications, with other opportunities for the graduates to develop technical skills and networking experience, practice business etiquette, and discuss career planning.

In this pilot year we’ve referred to individuals in this role as “interns.” Going forward we’ve decided to use a business title to better reflect the level of work and help participants penetrate the job market more successfully.

A new experience, but a familiar process

When we first considered launching a program like this, we thought there must be different things to consider when hiring and working with formerly incarcerated people, in contrast to people with no (known) criminal record. For example, would it be possible, or desirable, to limit the opportunity to people who had committed nonviolent crimes? What kinds of sensitivities and processes should we consider when assigning an intern to a team where an employee has disclosed that he or she has been the victim of a violent crime?

After much discussion among the foundation’s senior leadership and legal counsel, we decided to lean on the ethic of fair-chance hiring—which emphasizes offering people a second chance—as well as on the built-in assessment and due diligence practices that we follow during any recruitment process. Vetting candidates based on their motivations, interest, and career goals is already standard practice for us, as is conducting a background check.

Though we are fortunate to have a staff made up of people who were enthusiastic about the program and had some knowledge of the issues underlying it, it was still important to be candid and let staff ask questions openly. For those of us in HR, it was important to fully avail ourselves to any of our colleagues who had concerns. We found that Ford staff members were most concerned about basic etiquette—whether, for example, there were certain things they should be careful not to say or ask. It might sound obvious, we counseled, but they should treat these interns like any other co-workers—because that’s what they are. For all of us, this was an experience in confronting our own biases and assumptions.

Welcoming new colleagues

For our first cohort, we envisioned a group of three students, inclusive of both men and women. As in all our recruitments, finding diverse candidates was a priority. We were selective: We saw a number of very impressive candidates, but wanted to be sure that the opportunity we were offering would be useful to these specific individuals—that the work we do would be interesting and helpful to what each of them hoped to do next. In June 2016, we brought on our first class of three BPI interns. All three had earned associate degrees while in prison through the demanding and highly competitive BPI program; some had already completed, or were close to completing, a bachelor’s degree.

As the program advanced, we checked in with the interns regularly. Our colleagues at BPI were also in close contact. Working together, both our organizations wanted to be sure the interns were getting the most out of the experience, and that they felt supported. With this first class, we were especially interested in hearing what we might do better—what course corrections we could make along the way, as well as what we could learn to benefit the next class.

Now, as our first group of BPI interns complete the program, we’re helping them plan their next steps, providing professional job search coaching, emphasizing fundamentals like résumé-building, interview skills, and optimizing a professional online profile. For those interested in pursuing further higher education, we’re helping think about a plan for school and what might come after that. Of our first three participants, one is in the midst of a job search, one has been accepted to a program where he will continue his education in information technology, and one has been hired to a position with the foundation—in an area he didn’t realize he had an interest in, and aptitude for, before being exposed to it through a rotation.

This year has made us more conscious than ever of the importance of fair-chance hiring and diversity—and how it enriches the workplace to have a team of people with different experiences and backgrounds. As we’ve looked back on what we’ve learned throughout this process, we hope other employers will also feel encouraged to engage this high-potential-talent population.

In the meantime, we’re preparing to welcome our next group of participants. In perhaps the most telling adjustment we’ve made, we’re excited to be increasing their number to five.

Explore our guide to creating a re-entry program in your organization.