The untold stories of the women in Louisiana’s criminal justice system

“I needed help. But what I got was a sentence.”

After growing up in a broken home and seeing her mother struggle with abusive relationships, Dolfinette Martin was first arrested in Louisiana at just 16 years old. When it came time to leave prison and reintegrate back into society, she received little support and fell into a cycle that’s all too familiar for women in prison. “The trauma definitely led me to do the drugs which led me to commit the crimes which led me to prison,” she said.

Martin’s story is not uncommon. She is just one of nearly 2,000 incarcerated women in Louisiana. Across the United States, women are one of the fastest growing prison populations. Nationwide, the incarceration rate for women has grown by 834 percent in the past four decades. And in Louisiana, the state with the highest incarceration rates, the rate significantly outpaces the national average.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

Dolfinette Martin helped develop Per(Sister) and works as the housing director at Operation Restoration, a Ford grantee that supports women and girls impacted by incarceration.

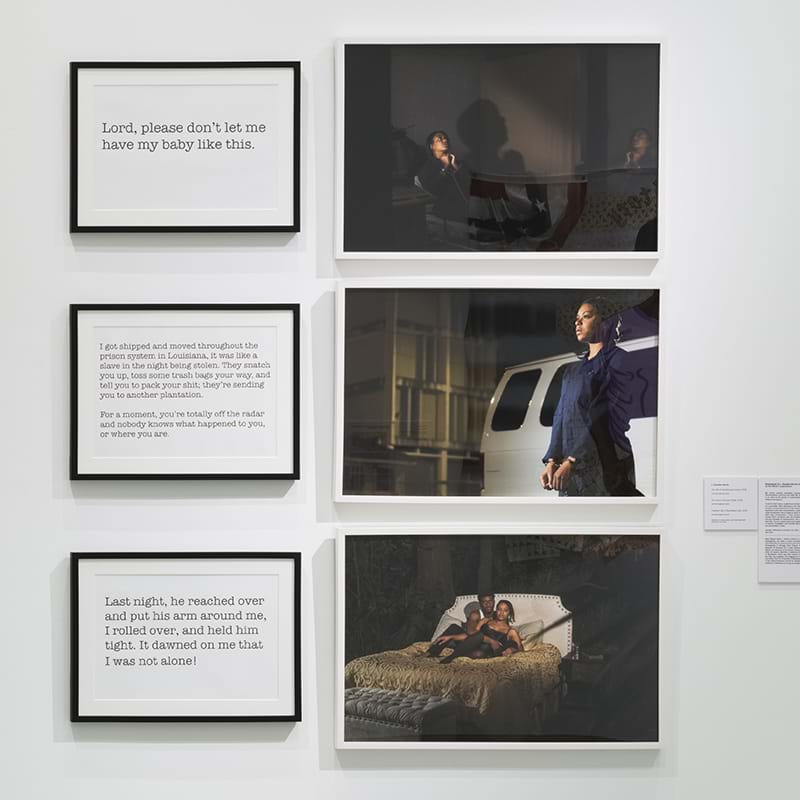

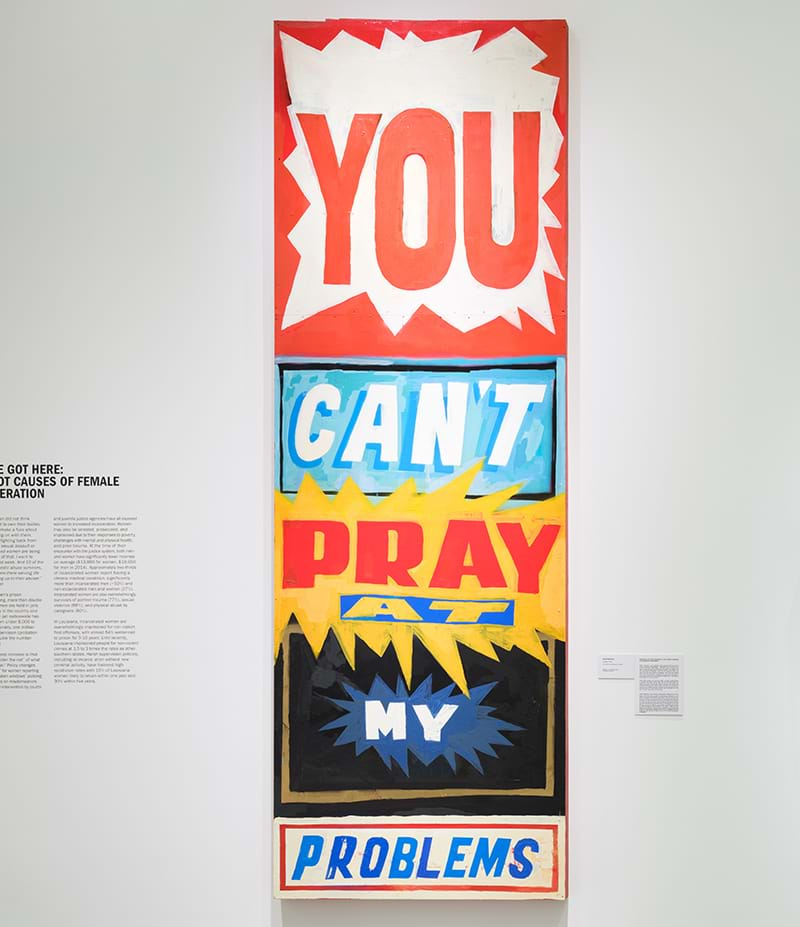

Our new exhibit at the Ford Foundation Gallery lifts up the stories of Dolfinette and 29 currently and formerly incarcerated women in Louisiana and the issues they face cycling in and out the criminal justice system. Created by the Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana features the work of Louisiana artists who, using a multitude of mediums, interpret the journeys of the 30 PerSisters—a title the incarcerated women have given themselves—before, during, and after prison. By illuminating their experiences, the exhibit, like Ford’s work in criminal justice, aims to challenge misconceptions and uninformed assumptions, build awareness and find common ground and paths for society to empathetically move forward together.

Newcomb’s museum director, Monica Ramirez-Montagut, and curator, Laura Blereau, conceived the exhibit with Dolfinette and fellow PerSister Syrita Steib, the founder of Operation Restoration, a Ford grantee that supports women and girls in Louisiana impacted by incarceration. Through a variety of artworks—including sculpture, photography, painting, voice recording, and song—and interviews with the women, Per(Sister) shed lights on the different issues at the heart of America’s mass incarceration problem.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

Installation view: Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana

How We Got Here: The Root Causes of Female Incarceration

A single parent who grew up in poverty, Dolita Wilhike struggled to take care of her children. To get her family basic items, she started to steal as a petty thief. By the time she was in her 20s, she was considered a habitual offender in Louisiana’s penal system, which lengthens incarceration by eliminating probation and early release for good behavior, while also increasing the maximum possible penalty for a crime.

With Dolita behind bars, her family found it hard to make ends meet. She remembers returning home after serving a sentence and realizing that her family hadn’t had running water in months. “It instantly put me back in the same position that I was in before I went,” she said. “I immediately wanted to go shoplift so I can earn some money to get my mother’s water turned on.”

She’s Somebody’s Mother: The Impact of Incarcerating Mothers

Fox Rich was an expecting mother with two children at home when she was arrested for jury tampering, facing 297 years in prison. When she finally was taken to the doctor, she went in for her ultrasound with handcuffs on and shackles around her ankles, flanked by an armed guard on each side.

“As I laid there in that cell in total solitude, I heard something that I had never heard before: it was the pounding of my heart,” she said. “And I thought to myself, that as long as I got life in me, then I’ll deal with whatever I have to deal with.”

Rich’s time in prison made her realize how imperative it is for the criminal justice system to consider how incarceration impacts not just the women charged with a crime, but the children left behind without their mothers. Currently, 2.7 million children in the US have a parent imprisoned. “When the father’s removed, it destabilizes the family,” she said. “When the mother’s removed, it decimates the family.”

Freedom and Justus, Freedom Day: A Boundless Love, 2018

A Place Not Her Own: The Physical and Behavioral Health Toll of Incarceration

Incarcerated at 19, Syrita Steib’s first memory of prison was seeing an ambulance parked outside the gate, at all hours. “So really early on, I associated this place with, ‘Nobody leaves out of here alive.’” Steib, who endured physical abuse at an early age, already felt like that experience changed the trajectory of her life. When she landed in prison, she was put in segregation, having to live through life-changing events like Hurricane Katrina and September 11 alone, unable to reach out to her family.

“People are not aware of the monstrosities that women face while they’re incarcerated, after they’re incarcerated, before they’re incarcerated, and just how the system continues to victimize you over and over,” she said.

After being released from prison, Steib realized her incarceration was just one part of serving her sentence—understanding how to start again, without any support, would be the next. “You’re releasing these broken pieces of women and human beings out into society, and you’re like, ‘OK, now go figure it out.’” she said. “It’s crazy, it’s not right, it’s inhumane.”

It’s her experience that led her to create Operation Restoration and build a support system for women and girls affected by incarceration. “If you fix women, you fix the world.”

What Comes Next: Challenges and Opportunities for Re-entry for Women

Being in the system is tough, but being outside can be even tougher. That was Lea Stern’s experience. When she left prison as a new mother, she had nowhere to go. “That is the absolute worst,” she said. “You lost everything. You have no clothes, you have nothing.”

When women are released from prison, they are often left without the tools and support required to build a new life. Because people cannot technically be released if there’s not somewhere for them to go, women scramble to get into programs just to secure their freedom. Once they arrive, however, the program isn’t always what they need or their safety is endangered—but they can’t leave or they risk violating their parole.

“You’re starting to try and start life over, and you have to live exactly how they want you to live,” she said. “You’re stuck at these places and you can’t leave because you’re there by probation…and then you’re in a bigger mess than you ever imagined.”

Every PerSister has her unique story, but they’re often woven from similar threads. By examining how women are incarcerated, the toll it takes on them and those around them, and how we, as a society, can better support them through re-entry, we can bring to light the cracks of a broken criminal justice system and truly see the people impacted who have been invisible, overlooked or misunderstood for too long.

As Dolfinette Martin said, “Women are in prison and we’re not there because we want to be there. Every woman or girl that goes to prison has trauma. We’re human. And we’re survivors. I am a survivor. I’m not a victim.”

Hear from all the PerSisters at www.persister.info.