“Hello,” wrote the anonymous source to a German newspaper, “this is John Doe. Interested in data?”

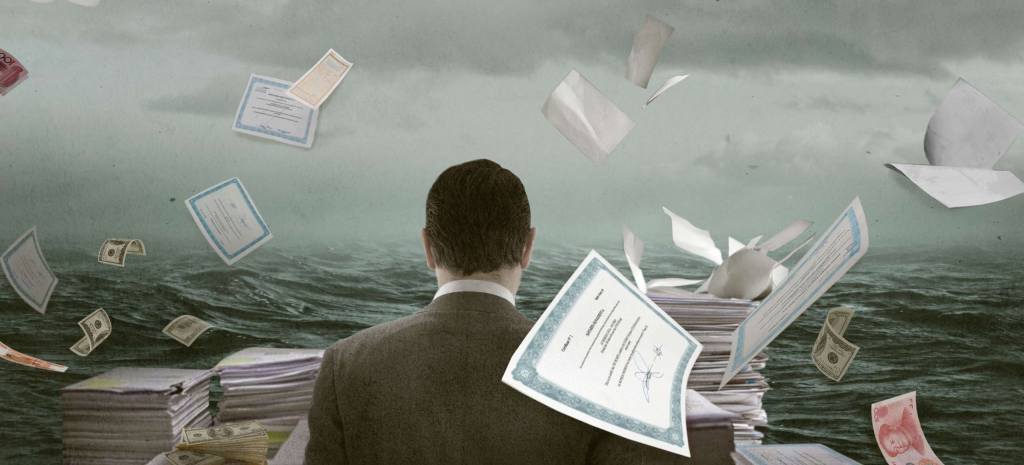

Thus began what would soon become an international financial investigation into what are being called the Panama Papers—an investigation so massive that even whistleblower Edward Snowden, on Twitter, called it the “biggest leak in the history of data journalism.” It involved hundreds of journalists in dozens of countries scrutinizing more than 11.5 million files—that’s more than 2.6 terabytes of data—in a massive trove of leaked documents belonging to a powerful law firm in Panama. Working diligently and quietly over the course of a year, this unprecedented network of journalists uncovered a shadowy web of tax avoidance schemes by world leaders, athletes, and celebrities around the globe.

This huge project was coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), a project of the Center for Public Integrity (CPI), which the Ford Foundation has long supported. At a time when the foundation is laser-focused on attacking systemic and structural inequality, we are reaffirming our commitment to centers of investigative journalism excellence that help people around the globe understand not only the “what,” but, as ICIJ has done with the Panama Papers, the “why” and “how” of inequality.

Before this latest investigation, the Center had coordinated several previous award-winning global investigations into financial secrecy—but nothing as big as the Panama Papers. Even before the first findings were public, Russian President Vladimir Putin attacked the ICIJ for asking why some of his closest associates had almost $2 billion flowing through offshore companies. Just hours after publication, Iceland’s prime minister resigned amid revelations that he had a secret offshore account while Iceland’s own banks were in meltdown.

I asked Gerard Ryle, director of the ICIJ, what the Panama Papers’ findings say about investigative journalism and global inequality more broadly. What follows is an edited and condensed version of our email conversation.

Barbara Raab: Of all the findings in this investigation, what surprised you the most?

Gerard Ryle: I think it was the large number of politicians and public figures we saw. Plus the integral role big banks and respected accountancy firms played in the offshore world. Then of course there was the data itself—the sheer scale of it. It was like a blow-by-blow account of the entire offshore world.

What do your findings reveal about inequality and about the ‘rules of the game’ when it comes to money, power, and privilege?

Generally speaking, what we witness in the documents is a flow of money from poorer nations into richer nations. We also see that those who can afford to play in this parallel universe are allowed to play by different rules. There was no doubt we were witnessing tax avoidance in some cases, and where taxes are avoided it means the average person has to pay more for the upkeep of hospitals and schools and public services.

The investigation reveals just how much these systems favor the rich and powerful. What would it take to disrupt those systems and structures?

If the richest nations in the world wanted to end the abuses afforded by secrecy— which is essentially the product that the offshore world sells—then it would end tomorrow. But what the documents show is the entire financial system has an interest in keeping the inequity going. In short, lots of people are making money on this. And while most of it may be perfectly legal, the illegal and immoral are taking advantage of the system.

Take us inside the investigation: What has life has been like for the past year, as the documents flooded in and the revelations began to unfold? What was it like to work on this project?

There were some amazing moments, but most of the work was rather unglamorous. Sifting through document after document, day after day, wondering if it was all going to be worth it. What we have learned is that you need to keep hold of your initial reactions to the documents—that excitement when you first see them. Because that initial excitement needs to sustain you through a very long journey.

In this case, the journey was over a year. Day by day, week by week, month by month, the enormity of the task seemed to grow as more media partners came on board and as we received more and more documents from the journalists at [the German newspaper] Suddeutsche Zeitung, who in turn were getting them from the anonymous source. They, of course, had their own pressures. They had to deal with the source.

Other reporters, such as the journalist from Iceland, had further worries. I like to describe our Icelandic colleague as the loneliest journalist in the world. For 9 months he knew he had information that could bring a government down—and eventually did—but he could not tell anyone. He could not even earn a living, because he refused all other work as a freelance journalist so he could concentrate on this.

How did all the journalists involved in this project communicate with one another, and how was their information kept private?

We required all of the journalists to use a virtual newsroom that we set up specifically for the project. So every day, each reporter would go to their physical offices but they would also go to the ICIJ virtual office. Think of it as a Facebook for journalists. There they could report their findings, form groups around certain topics, swap tips. It was important that we also go outside the documents, to court records and other kinds of public records. The virtual newsroom was also the place where we could upload and share those kinds of documents.

In the wake of the widely seen, Oscar-winning movie Spotlight, which went inside the Boston Globe’s investigation of sex abuse by Catholic clergy, and now the Panama Papers, are we seeing a “golden age” of investigative journalism?

This is an era of big leaks, so that is a bonanza for journalists. Without information, we can’t do our jobs—because without information, we can’t look for patterns to discern matters of public interest. This is also an era of easy and cheap communication. It would not have been possible for us to do this investigation 5 or 10 years ago. And because this is the era of big data, there has never been a better moment to bring hundreds of reporters together to get their collective eyes on things. I think we have proved with this project that there are plenty of stories for everyone. And that by working together, at least on certain stories, you do get a better result.

What’s important for funders to understand about this kind of work?

Good journalism takes time. And the best way to get media partners on board for big collaborations like this is to choose the right topics. We are incredibly grateful for the long-term support of our donors and their partnership in developing the network that has made this possible. If a donor is after impact, we think we have delivered it.