Photo by Flickr user dany13

Photo by Flickr user dany13Recently in Rio de Janeiro I had the chance to visit a membership-only club, located on the shores of the beautiful Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon. It was my first time at the club; I was accompanying a friend’s daughter who plays sports there. I felt a combination of dazzle and discomfort—even as I was treated courteously by the staff, it was as if, at any moment, I might be unmasked as someone who didn’t belong. But the day was beautiful, the view inviting. The warmth of the morning sun caressed my face. And so I relaxed, sat on the edge of the lagoon, took some photos, and paged through a book, hoping to enjoy a few hours of reading in front of that breathtaking landscape.

Yet I could not stop thinking about my initial discomfort. It nagged at me. What had caused this feeling of displacement? This was not my first time in an elite space. And I’m actually accustomed to feeling like I don’t fit in with those kinds of environments. Life has given me opportunities to be in places of power and privilege, where people of my origin—black and suburban—are rarely seen. The position I hold today, as director of the Ford Foundation’s work in Brazil, not only opens up my access to these spaces of power but also requires a constant state of alertness about my own place of privilege.

Still, all this experience did not help me escape the uncomfortable feeling that I was invading a space where I was not welcome. What was this feeling about?

The club was a space reserved for those who share a deep bond based on their class and race: a place of exclusivity, for white people of the upper middle class and a wealthy few. I thought perhaps my discomfort was due to the fact that I did not feel “entitled”—I lacked this sense of having an almost natural right to be there. I imagine it does not cross the minds of the club’s members that they might not deserve their place there and what it has to offer: the privilege of being among relative equals, in the midst of one of the most unequal societies in the world.

Over the nearly two hours I was there, I did not see a single black man or a black woman who was not working in a service capacity (as a nanny or waiter, for example)—except for myself. It struck me that the peacefulness of the club—the tennis courts and soccer fields, the swimming pools, the sailboats docked in the hangar, the tranquility and the carefree atmosphere, the calm with which members walked—was a product of a comfort and intimacy made possible by the indelible bonds of privilege.

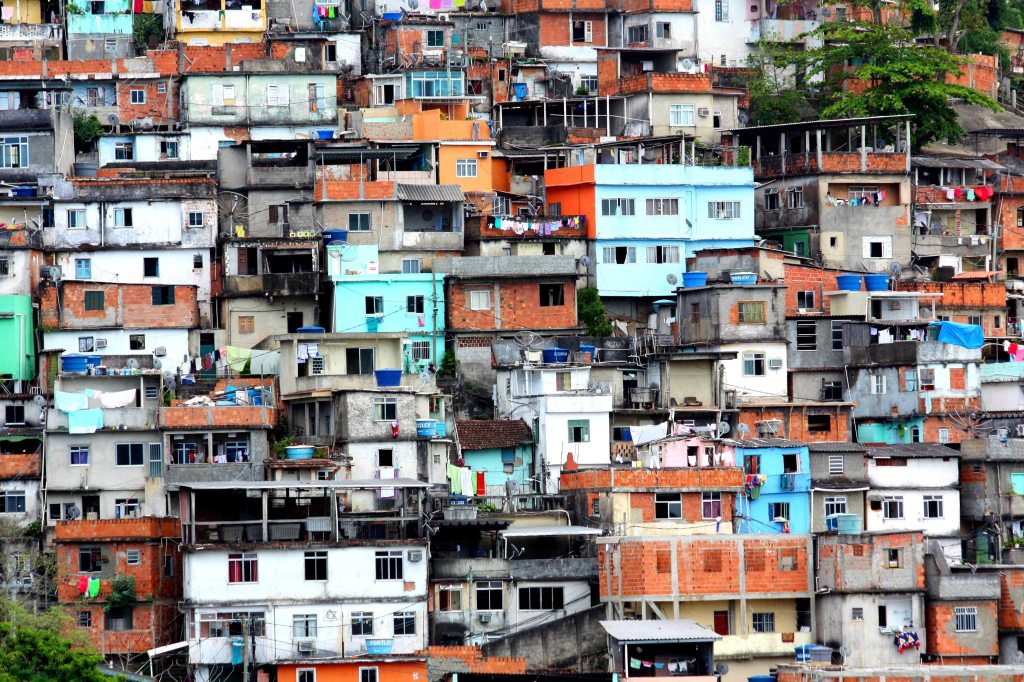

It is very good to be rich and white in Rio de Janeiro, even in moments of social and political distress. From the vantage point of exclusive resorts, clubs, condominiums, and upscale restaurants, privilege offers a unique view of a complicated landscape, a view without disturbance, danger, or too much noise. This is true even if just few miles away, in one of the many favelas in the heart of the city, extreme violence is disrupting (and in some cases ending) other lives. In this city, the epidemic of homicide requires an epidemic of indifference. The state of Rio de Janeiro sees an average of 16 homicides a day, a vast majority of them in the favelas and other poor neighborhoods. Most of the lives lost are those of young, black men.

Privilege is very comfortable. But fighting the kind of inequality that leads to great suffering for so many will require disrupting that privilege, and breaking down some of the barriers that enable and preserve it. About a decade ago, when Brazil’s quota policy was first implemented, it helped make higher education possible for a population of young people who, until then, had not imagined it could be a part of their lives. The reaction was brutal: fierce words of resentment and accusations of “reverse racism,” arguments that quotas contradict merit and would lead to a decline in academic quality, and so on. We still hear those arguments today, despite the fact that student performance has proved those critics wrong. The quota policy, and others like it, make people uncomfortable—especially people who live with privilege, and take their advantages for granted. But these policies also make a difference, opening up possibilities for people who, through no fault of their own, have less privilege, and therefore less opportunity.

It is necessary to challenge the status quo and to build a new, more diverse, and inclusive kind of normal. We must open spaces for the leadership, creativity, and beauty of the young people who live on the periphery, in the favelas and other neighborhoods. We must listen to the voices and demands of the young women who are reinventing political action and the struggle for rights, and achieving successes that were unimaginable not so long ago. Movements for justice must be movements for all. We need space for black artists, writers, directors, actors, curators, and creators, so that their voices expand and enliven the stories we see in film, online, and on TV. We must create the conditions for popular entrepreneurship to flourish, so it can help reinvent the local economy and produce circles of cooperation, which have enormous potential to generate wealth. (Anyone who has ever approached the economic life of a large favela knows what I’m talking about.)

This will require the effort of everyone in Brazil, including the most privileged. For opportunity and rights to be more widely shared, we need people with privilege to recognize that they are not the only ones entitled to those things, and that their privilege can be used for the good of others. The discomfort I felt sitting at that private club was useful. Perhaps others might do well to take on some discomfort of their own, as a way to begin to recognize and confront the inequality that ultimately does so much harm to all of humanity.

Just as important, realizing change will require that people who have been excluded and discriminated against—“outsiders” of all kinds—are empowered to have a voice in the decisions that affect them, and in the life of their broader society. It is only when these less privileged people are visible and active that those who have always been protected by the invisible walls of social exclusion will recognize that they are not the only ones entitled to rights. This will probably be uncomfortable—but discomfort is a sign of progress. Indeed, it is a precondition for it.